Haworth Moors, Yorkshire. © J. Ashley Nixon

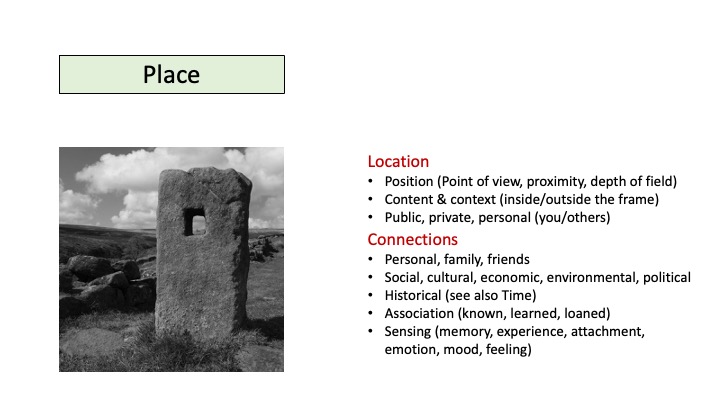

Put simply, photographs use light to record moments in time and space. We can define this precisely in terms of a second, a minute, an hour, a day, and a year. We can locate a site anywhere on Earth with its latitude and longitude coordinates, or even through a set of three words. But to explain a place rather than a space needs more than mathematical points on a map (the “where”). We need to describe their physical characteristics (the “what”) and their social, emotional or cultural relationships with people (the “why”).

Compass and map (OS 104: Leeds & Bradford). © J. Ashley Nixon

Interpreting places with photographs

Photographs, with or without words in titles, captions, and supporting text, help us relate to, understand, and represent places in the world. They record experiences that we can transmit and share almost instantaneously, or return to decades or even lifetimes later, on screens or as prints, to create associations or invoke memories of what, when, and where things were happening.

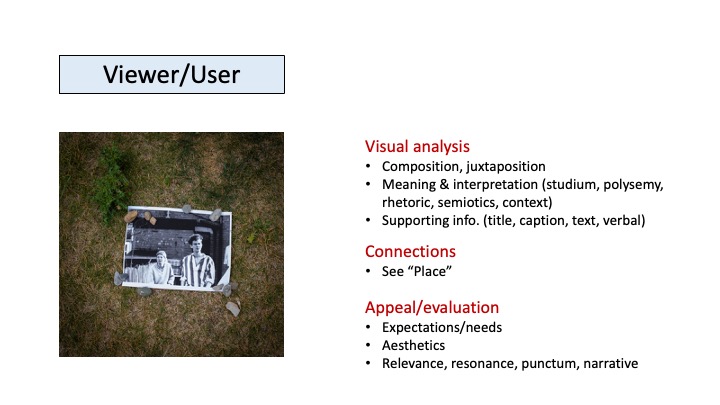

Given the polysemic nature of images and our diversity of thinking, the meaning of a place shown in a photograph may resonate with us in ways that are commonly felt by others or in a more personal, powerful manner. Roland Barthes described this as the studium and punctum of a photograph in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980). The studium (Latin for study) refers to the subject, meaning and overall content of the photograph, which viewers tend to observe in common. The punctum (Latin for point) is something more personal that registers with us individually and which may encourage a longer look and moments of reflection as we interpret and connect with the image. The more punctum found in a photograph, the more likely it is to be an impactful image.

Place and landscape

The very word landscape is anachronistic.

David Bate (2016)

David Bate, in The Key Concepts of Photography (2016) says: “It is a wonder that we are still able to use the term “landscape” at all. It is so strongly rooted in particular traditions and histories of European painting and Anglo-American art and photography that it begins to feel like even the very word landscape is anachronistic. It is a word, let alone a concept, that does not seem to have kept pace with the times we live in.”

If genre is important to you (yes, these words conveniently help to categorize work, but can be restrictive), could an image of a place be better classified as a portrait, or as a form of documentary photography rather than a landscape? And with more than half the world’s population now living in cities, are we better off saying urbanscape? Or should we get into the weeds by using words like, let’s push it (pun intended), shoppingtrolleyscape?

A shopping trolley in a winter urbanscape. © J. Ashley Nixon

The “beachscape” work of Martin Parr, such as in The Last Resort (2017), serves as a reference point for amusing, yet at the same time, serious (satiric, ironic, sharp-eyed?) vernacular photography around holiday destinations and leisure places. Parr’s images have less to do with showing off “nice places”; they are more about raising questions about society, such as excessive consumption.

Martin Parr (2017). The Last Resort.

Opposed to the beautiful spots featured in “conventional” landscape photography are the abandoned buildings, burned-out cars on derelict land, and other grim places that are legitimately included by photographers trying to make sense of life in city places.

Derelict building, Detroit, MIchigan, USA. © J. Ashley Nixon

Photography making sense of place

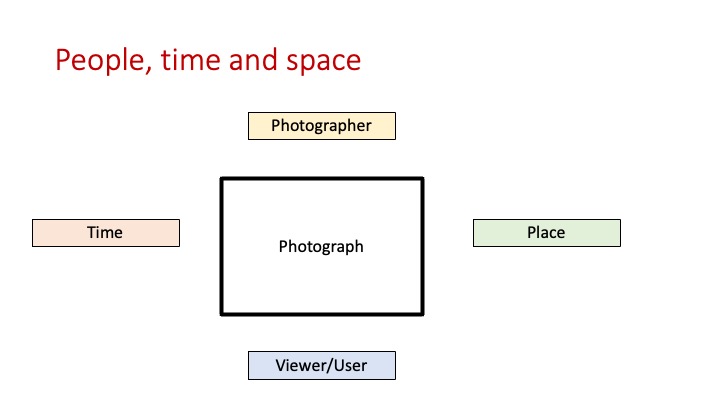

What are the roles and interactions between the photographer, place, viewers, users, and time when making sense of a place with a photograph? Let me try to answer that through a series of diagrams.

Photographs record moments in time that can usually be related to spatially.

Photographs help us to relate to and understand places in the world.

The purpose of a photograph determines how it represents a place. A photograph casually taken on holiday serves as a personal reminder; a commissioned project will likely meet the needs of a contract, for example, a publication and its users. Between these two situations lies the personal project of a photographer seeking to find meaning in a place. It could be their own viewpoint, or an effort to represent those associated with it, such as by birth, residence, employment or recreational connection.

Purpose triggers an approach to photographing that demands a level of empathy, integrity, and authenticity appropriate to the location and circumstances. This might require seeking permission to photograph and local involvement in the process (more on this in future articles about community and place and photographing people who have no place to live).

A moment clicking the camera. A lifetime figuring out when and where to do it.

It takes a moment to click a camera, a lifetime to figure out when and where to do it. The skills and experience required for a photographer to get the best outcomes from their opportunity will likely go beyond photography itself: social engagement, political acumen, and environmental knowledge are just a few examples.

To define a place rather than a location, we need more than mathematical points on a map (the “where”). We need to describe its physical characteristics (the “what”) and its social and emotional relationships with people (the “why”).

Estate agents (aka realtors) love to say location, location, location about home places. Indeed, a well-composed photograph, mindful of light and shadows, depth of field, what is inside and outside the frame, and other photography chops, will help to communicate a story. But composition is not the story, and for plenty of photographs of place (but not all), the person behind the camera is more important than what is in front. How does the photographer create an image that connects with and invokes a response from others? As previously mentioned, this is driven by purpose (see above) and how a photograph is used.

Given the polysemic nature of images and our diversity of thinking, our interpretation of a place in a photograph may be the same or different from that of others.

A user’s analysis of a photograph may be casual or in-depth. Both are good and proper, and it’s fair to say that most pictures are looked at quickly, and life moves on. As a university teacher, it’s my challenge and opportunity to get my students to take a deeper dive into the meanings associated with an image and how a composition helps reveal a narrative and tell a story.

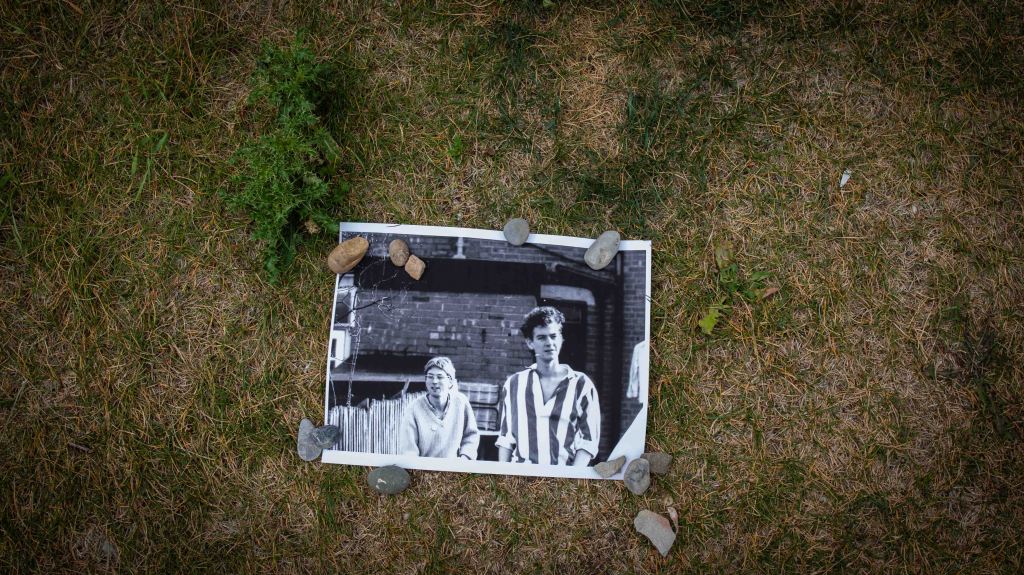

University friends © J. Ashley Nixon

Take, for example, the photo shown above. With a few seconds of effort, most people will see a photographic print held down by a few small stones. A moment later, you see two people; one has a stripy shirt. There’s a wall behind them. Perhaps it’s a garden. And then a question to oneself: what is the print doing on the grass? Why are the stones there? What do they mean? Only a few people (the subjects, their families and the photographer) will get the point (punctum) of the photograph. Others might only look for a moment, perhaps gathering some ideas about what is going on (the studium).

All photographs are polysemous; they are open to multiple interpretations. Some are rhetorical; they persuade a way of thinking. Some are intriguing, like this one: a photograph of a photograph that seeks to make connections between people and places across time that only a few will ever really understand.

We can relate to a place temporally. This might be a moment, or much longer and we may relate this to other times and places in our memories..

We can, and do, connect with places in time. A moment captured in a photograph may release a bundle of memories in a viewer of that place, of other places, and of related experiences. It may be a decisive moment, a well-known photographic expression attributed to Henri Cartier-Bresson and appreciated by many street (and sports) photographers. Or it may promote a recollection (even a stronger memory) of what happened before or after the situation shown. The context of a photograph, and the association of time and place, may be immediately apparent from a single image, or it may require additional ones or words, written or told stories, to better understand the meaning of a photograph of a place.

Places that make us

Photographers making sense of place draw upon the full range of sublime to beautiful (or even both) to create meaning as they tell their visual stories about places where we live, work, play, and create joy, harm and conflict. How we respond emotionally to such represented places is a fascinating subject of behavioural science research. One study, commissioned by the National Trust, focuses on human responses to aesthetically pleasing places.

The National Trust (NT), founded in 1895), is a conservation charity independent of the government that cares for hundreds of places across England, Wales and Northern Ireland for their landscape, conservation and historical values. The NT commissioned research by the University of Surrey and Walnut Unlimited (National Trust 2017) to understand the depth of connection people have with place using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and behavioural studies. Twenty people were examined using fMRI to see how their brains reacted as they looked at images of objects and meaningful places. (A meaningful place was defined as a place outside of the home, i.e., not a person’s home, with which they have a strong emotional connection. These included woodland areas, coastal areas, buildings and historic sites.) Some photographs were chosen by the subjects for their personal meaning. Some were selected by the researchers. A third set of images came from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS), quantified for their emotional content (positive and negative).

Neurophysiological research (using fMRI) found that viewing images of meaningful places creates a significant emotional response in the brain’s core emotion-processing areas.

In the second stage of the study, 11 people were interviewed in depth to collect rich accounts of their connections with meaningful places and the language they use when talking about them. In the third stage, an online survey of over 2,000 people was conducted to quantify the link between people and places. Respondents were asked to describe a significant place, why it was special to them, its benefits, and the feelings it evoked. The participants were also asked what it would mean to them if this place no longer existed and how important it was to protect it.

“From the place of your earliest memory to a setting which invokes memories of a loved one, we all have places that are intensely meaningful to us. There are places where we feel calm or that provide us with space to think; places we feel a deep pull towards or that have a physical effect on us when we visit; places where we feel ‘at home’ or that make us feel complete.”

National Trust (2017)

What type of place do people connect with?

Of those surveyed, 42% spoke about urban locations such as sports venues, schools, and their home villages, towns, and cities. 21% described semi-rural and natural places, including woodlands, stately homes, mountains, and beaches. The remainder described specifically named places in the UK, such as Yorkshire, or elsewhere, such as Greece.

How are connections formed?

The study (updated in Why Places Matter to People, National Trust, 2019) revealed how people connect with places differently and at various points in their lives. One research subject said of Wycoller, a place I recall from my own childhood:

“I first remember coming to Wycoller village when I was 6 or 7. I’ve got a lot of memories here of playing amongst the ruins, with my brother and sisters, while my parents watched me. It has made me who I am today, and whenever I visit those memories come flooding back.”

Frances, Lancashire (National Trust, 2017)

Three categories were generated: 42% showed connections to their formative years, 37% linked them to significant others, and 41% connected to places that don’t focus on significant people or moments in their lives, what the report calls the “here and now.”

Feelings evoked

Some of the key words associated with places were:

- Calm: 64% agreed that their special place makes them feel calm.

- Joy and contentment: 63% agreed they feel joy and contentment when visiting their special place.

- Energy: 28% mentioned that their place makes them feel energized.

- Discovery: 14% recognized the value of exploring a place and the potential for adventure.

- Identity and Belonging: When asked what the place means to them, most respondents (86%) said, “I feel like this place is part of me.” 76% said, “Visiting this place says a lot about who I am.” 58% said, “I wouldn’t be who I am today without this place.” 58% said, “This place has shaped who I am.”

Benefits of visiting places

In addition to evoking emotional responses to special places, feedback from the participants in the study revealed how we benefit from visits in terms of mental well-being, such as helping to find perspective, a feeling of rejuvenation, escape from everyday life, refocusing the mind and giving headspace. One research subject said:

“The moment I enter the park the stresses from everyday life just leave me and I have space to think. I forget about the chores and my work and just enjoy the space. When I haven’t visited all week and I’m grumpy my wife jokes that I need to go to the park and relax.”

Bello, London (National Trust, 2017)

Nostalgia is another benefit of visiting special places. It is important to provide “a stable sense of self and allow people to compare their present and past self, which has a restorative impact on aspects of psychological well-being such as self-esteem.” (Sedikides et al., 2015).

Many participants also expressed the sense of being in a “safe place” as a value (60%). Safe includes mental safety (emotional security, refuge, and comfort), which is attached to fondness and familiarity with a meaningful place, and physical safety, which is particularly important for people responsible for caring for children or other vulnerable individuals.

“Meaningful places have a positive effect on our well-being.”

National Trust (2017)

In concluding their study for the National Trust, the researchers said, “This research set out to gain an in-depth understanding of the deep connection people have with places. We have demonstrated that there is a strong physical and emotional connection between places and people and that these places have a positive effect on our well-being.”

Photographers making sense of place

The following section examines some photographers who have made, or are trying to make a sense of place in their work.

Another Place

Iain Sarjeant established Another Place Press, a small independent publisher based in the Scottish Highlands, in 2015. They showcase the work of contemporary photographers, including through Field Notes, a series of limited-edition photo zines. Impressively, the series has included 72 publications from photographers around the world. Here are some examples:

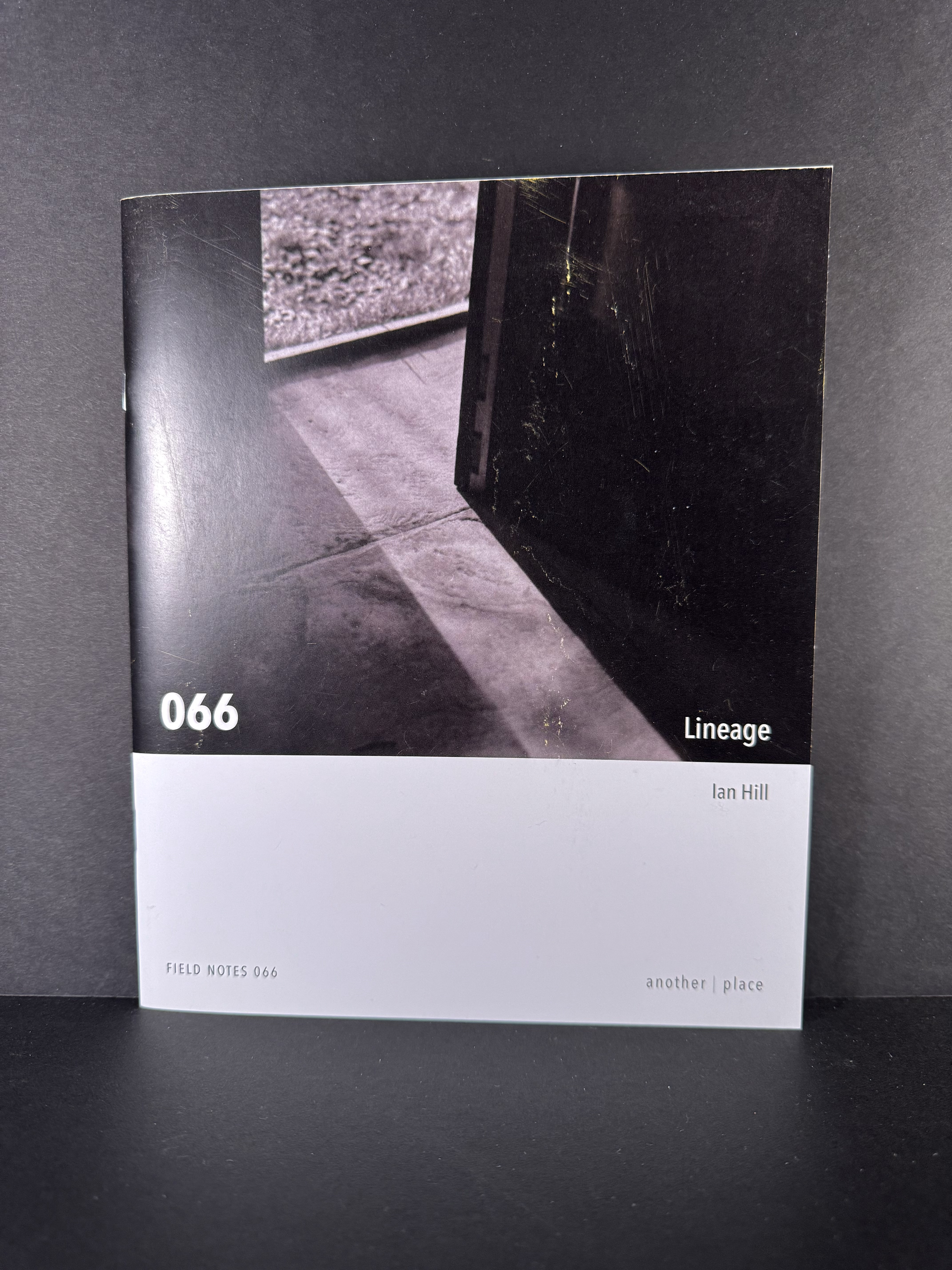

Another Place Field Notes (left to right): Lineage by Ian Hill, North Sea Swells by Joanne Coates, FarmerFlorist by Tessa Bunney.

Lineage

Lineage by Ian Hill (Field Notes 066) (Hill, n.d.) is an inquiry, in words and images, into Allerdale, Cumbria, and examines the landscape as a palimpsest, a succession of layers (of people, places, and activities) added over time, building on the past and influencing the people who follow.

“What are we seeking when we try to understand our place in the world?”

Ian Hill (n.d.)

North Sea Swells

North Sea Swells by Joanne Coates (Field Notes 021) (Coates, n.d.) was inspired by her trips to the Yorkshire coast with her grandparents. It features the work of fishers onshore and in their boats, risking their lives to make a living as they navigate places in the North Sea.

FarmerFlorist

FarmerFlorist by Tessa Bunney (Field Notes 06) (Bunney, n.d.) explores workers on small flower-growing farms in Britain responding sustainably to a market for “fair trade in flowers.” In a recent publication, Going to the Sand (Bunney, 2023, released by Another Place (outside the Field Notes series), Bunney photographed and recorded conversations with fishing families in the splendid, ever-changing landscape/seascape of Morecambe Bay in NW England.

In-between Places

Everyone deserves a place called home, but not everyone has that opportunity. People experiencing homelessness are bound to a transient life—an alleyway here, a park bench or a shop door there. Long hours intervened, perhaps, by some time in a shelter: out from the deep cold, the snow and rain (if you are unfortunate to be homeless in a Canadian city), or the searing sun if your travels take you further south. Then, back out again, a new day and another place to try and survive. Repeat.

Landscapes for the Homeless

Anthony Hernandez has developed an empathetic approach to photographing people experiencing homelessness in his hometown of Los Angeles. Moving from black-and-white to compassionate compositions with rich colours, he extends “a dignity, so often denied by other parts of society, to the temporary inhabitants of these spaces” (Alexander, 2020, p. 175).

“Hernadez brings order to the chaotic scenes he encountered, humanizing the absent subjects by paying attention to what they left behind.”

Erin O’Toole (2017)

People are absent in his Landscapes for the Homeless (1996). “With his dog, Frida, by his side for company, Hernandez sought out sites where homeless people had recently slept, entering during the day so as not to disturb anyone. Through precise framing, Hernadez brings order to the chaotic scenes he encountered, humanizing the absent subjects by paying attention to what they left behind, much as an archaeologist would.” (O’Toole, 2016).

Erin O’Toole (2016). Anthony Hernandez.

Altered Places

Industrialization, urbanization, unfettered resource extraction, pollution and climate change have all taken their toll on nature and influenced how the “natural landscape” is photographed.

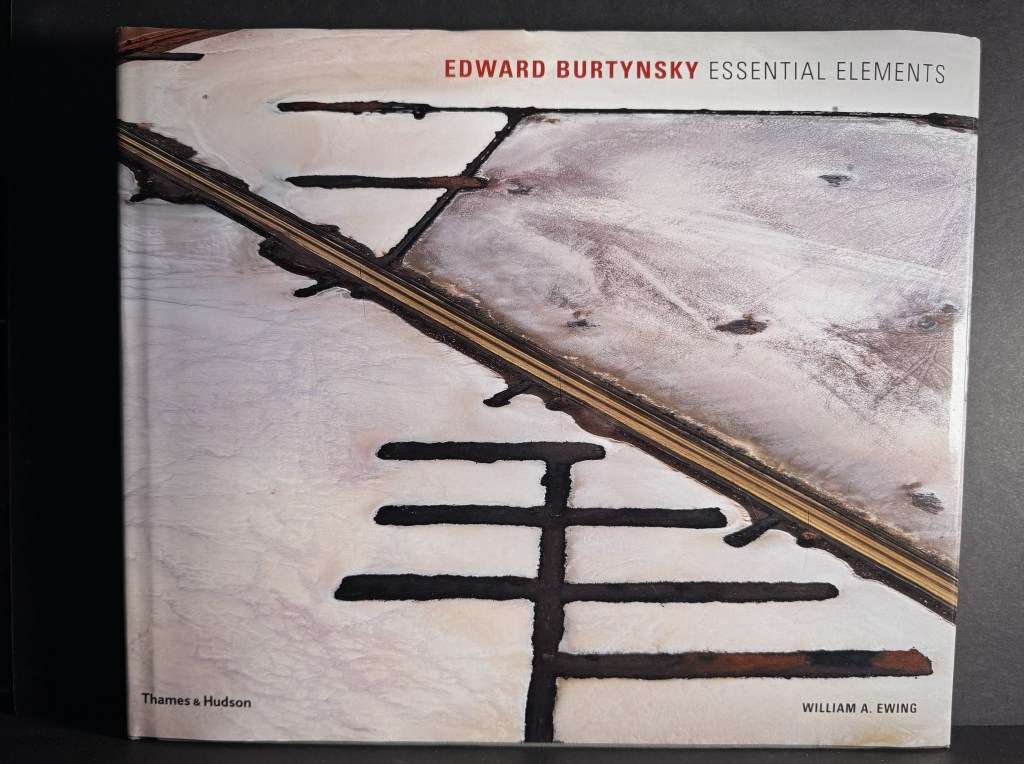

Essential Elements

The massive, printed works of Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky showing human impacts on the environment in Essential Elements (Ewing, 2016) and Anthropocene (Burtinsky, Baichwal & De Pencier, 2018) are persuasive examples.

William A. Ewing (2016). Edward Burtynsky: Essential elements.

Essential Elements provides an overview of Burtynsky’s work over four decades which has included a wide range of projects turning out books and films with titles such as Quarries (1991-2006), Oil (1999-2008) and Water (2009-2013). Anthropocene is a collaboration between Burtynsky and two other artists and filmmakers, Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier. With a multimedia approach using photography, a documentary film and a series of exhibitions, their project invites viewers to bear witness to how planet Earth has been irrevocably transformed by human activity (Burtinsky, Baichwal & De Pencier, 2018, p.10).

Geologists and other scientists from the Anthropocene Working Group, established by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) advocated that the World had moved out of the Holocene and into a new epoch called the Anthropocene. Their case was based on widespread evidence of the Earth being massively transformed, across geological time through urbanization, agricultural and industrial activities that have led to the profligate use of plastics and cement, massive rates of deforestation and species extinction, and the pervasive consequences of climate change.

“The Anthropocene will remain an invaluable descriptor in human-environment interactions.”

IUGS, 2024.

Although the case for a new epoch was rejected, in a vote by the IUGS in 2024, the IUGS acknowledged that: “The Anthropocene as a concept will continue to be widely used not only by Earth and environmental scientists, but also by social scientists, politicians and economists, as well as by the public at large. As such, it will remain an invaluable descriptor in human-environment interactions.” No doubt, the Anthropocene will serve for some time to come as a time dimension with which to describe many of these altered places.

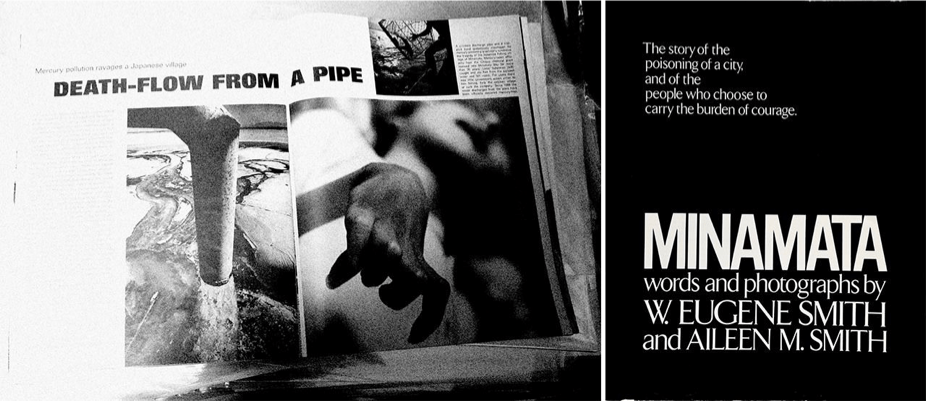

Minamata

W. Eugene Smith and his wife, Aileen Mioko Smith, went to live in Minamata, Japan in 1971. They investigated the health impacts caused by mercury contained in industrial effluent released over decades from the Chisso Corporation chemical factory into Minamata Bay. The metal bioaccumulated, as methylmercury, within the food chain and was consumed in the fish eaten by people in the area. The neurotoxin, transmitted from mothers to babies during pregnancy, affected brain and nervous system development in unborn children, resulting in devastating physical and mental damage. Minamata Disease afflicted 2,265 individuals in the area, and 1,784 died as a result.

Gene and Aileen Smith expected to be in Minamata for three months. Their time there turned into three years. Minamata would be Smith’s last photo essay, published in LIFE in 1972, and a book Minamata, coauthored with Aileen (Smith & Smith, 1975). Both are profoundly important in the discourse on environmental pollution and eco-toxicity. While Smith’s harrowing photographs of the victims were effective in raising political awareness of this dreadful disease, it took until 2017 for the UN Minamata Convention on Mercury (protection of human health and the environment from the anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury) to come into force.

W. Eugene Smith and Aileen M. Smith (1975). Minamata.

Mercury is still used in some industrial processes and in extracting gold ore. In the late 1990s, I witnessed some of the huge ecological and health impacts of artisanal gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Disturbingly, over 200 tonnes of mercury are still released every year into the largest river catchment system in the world (Crespo-Lopez, 2021).

Place to Place

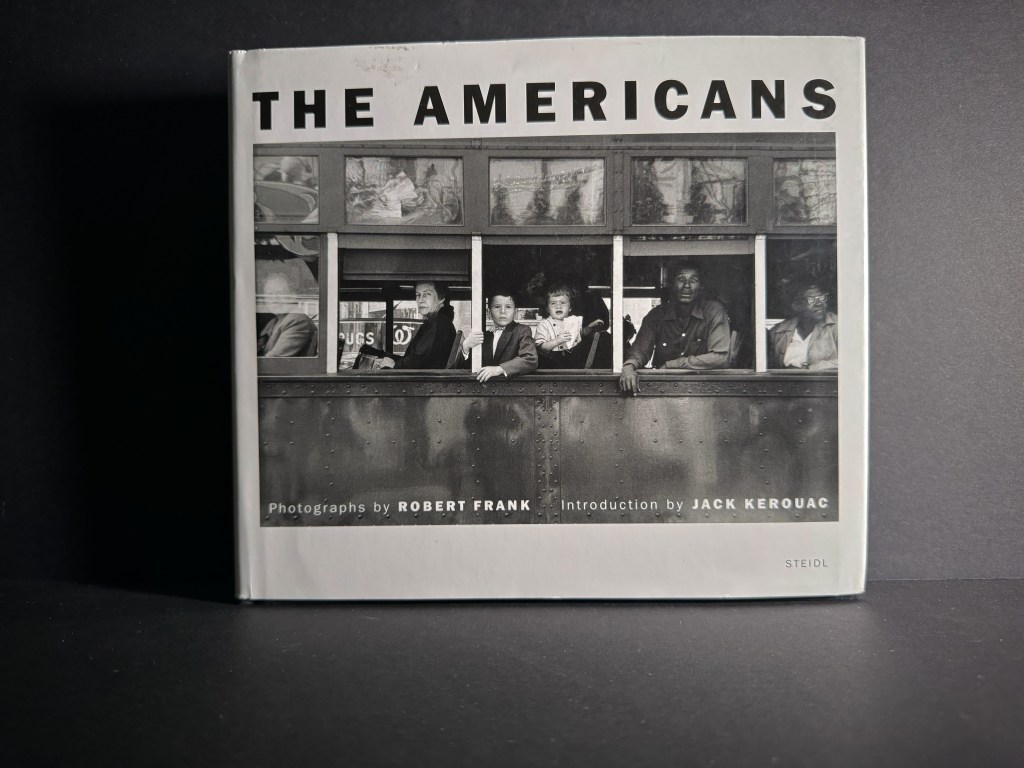

Road trips have made a considerable contribution to the study of places. A good starting point is The Americans by Robert Frank (Frank, 2019).

The Americans

The Americans, originally published in 1958, is based on a 10,000-mile journey that began in New York in 1955 and took in cities across the USA such as Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, Las Vegas, New Orleans, and Miami.

“The Americans reveals the politics, alienation, power, and injustice at play just beneath the surface.”

National Gallery of Art (n.d.).

Frank, born in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1924, was an immigrant to the USA, and with that came an outsider’s vision. The Americans has a thematic sequence comprising 83 selected images (he shot more than 27,000 on film) that “reveals the politics, alienation, power, and injustice at play just beneath the surface of his adopted country” (National Gallery of Art).

Robert Frank: The Americans (originally published 1958).

Book of the Road

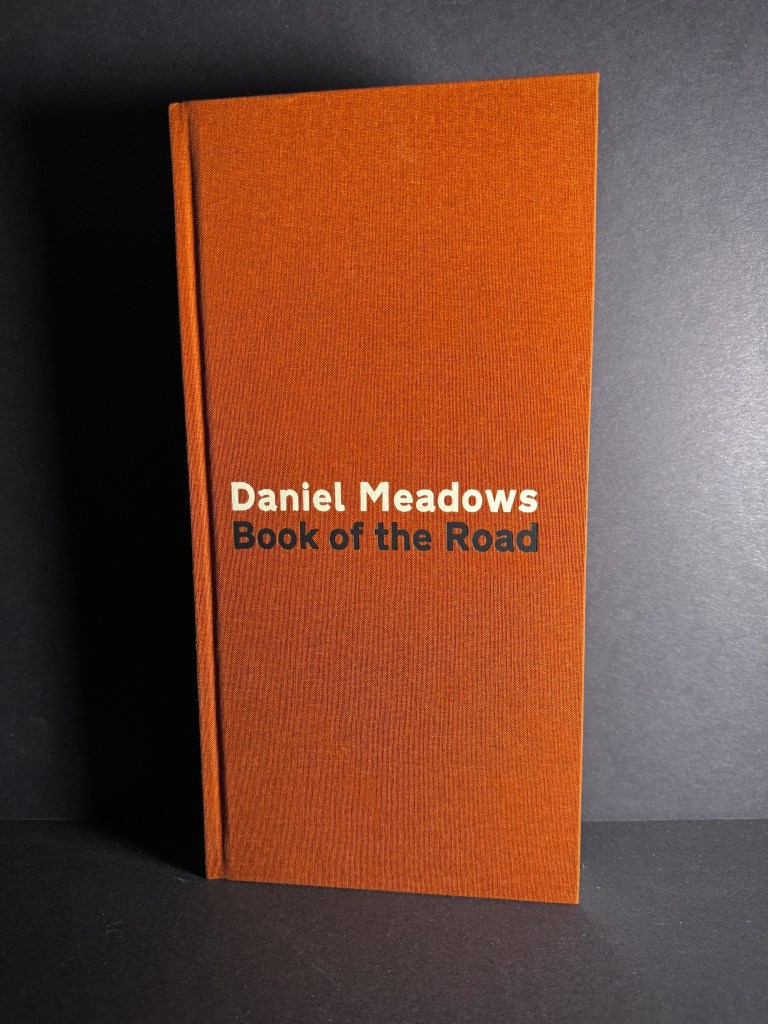

Book of the Road by Daniel Meadows (Meadows, 2023) celebrates the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Meadows’s road trip around England in a 1948 red double-decker bus, repurposed as his home, gallery and darkroom.

Daniel Meadows (2023)

“For all the people.”

He called his bus The Free Photographic Omnibus because “I had done Latin at school and I knew that ‘omnibus meant ‘for all the people’.” (Meadows, 2023, p.10). In a journey of 10,000 miles, he photographed 958 people, providing free portraits from his mobile studio as he went. He also did photo reportage and made audio recordings. It is a book of portraits of people in places (he visited twenty-two villages, towns and cities on his journey) whose “quality of life is threatened by the apparent necessity for social change” (Meadows 2023, p.5). Book of the Road also contains, in lovely pull-out flaps, photographs taken in the 1990s of some of the people he originally met on his first excursion on the bus, alongside their quoted responses.

“We are reminded just how much human feeling has travelled unchanged through time and across the generations.”

Tom Booth Woodger

Tom Booth Woodger, the designer and editor of Book of the Road, says it celebrates “the intricate cartographic force of the original book” (The Bus: The Free Photographic Omnibus, 1973-2001, published by Harvill Press in 2001). He continues, “[We] are reminded just how much human feeling has travelled unchanged through time and across the generations.” It’s a splendidly designed book that those of a certain travelled age will instantly recognize, from its brown cloth binding, fonts (Transport and Skolar) and shape, as a homage to the Reader’s Digest AA Book of the Road (1967).

Daniel Meadows (2023). Book of the Road.

English Journey

Another beautifully designed and rendered book of places is English Journey by John Angerson (2019). It pays tribute to the book of the same name published by Bradford-born J. B. Priestley in 1934.

Being a rambling but truthful account of what one man saw and heard and felt and thought during a journey through England.

J. B. Priestley (1934). This is the sub-title to his book English Journey.

Following the same prescribed route as the novelist and playwright before him, Angerson ventures from Southampton in the south, west to Bristol then up through the Midlands and north of England before turning back to Norwich in East Anglia.

John Angerson (2019). English Journey. The book cover and a postcard given to me by the author. This shows the photograph featured in the West Riding of Yorkshire section of the book: a stretched Hummer limousine outside the Bradford Registry Office.

Each of the places visited is marked on a pull-out map; each location is represented with a photograph of a place or a person, splendidly mounted to the page in a manner rarely seen.

Americanisation and homogenisation seem to penetrate almost every town and city.

John Angerson

Angerson notes some of the changes in England since Priestley’s time: “Americanisation and homogenisation seem to penetrate almost every town and city…Celebrity culture and its media stronghold is fast becoming a national obsession.” Less critically, he observes the human, open-hearted spirit of the people he encounters: “[W]e work as individuals towards a common goal of cooperation never forgetting that we are all dependent on one another.” (Angerson, 2019).

Novel Places

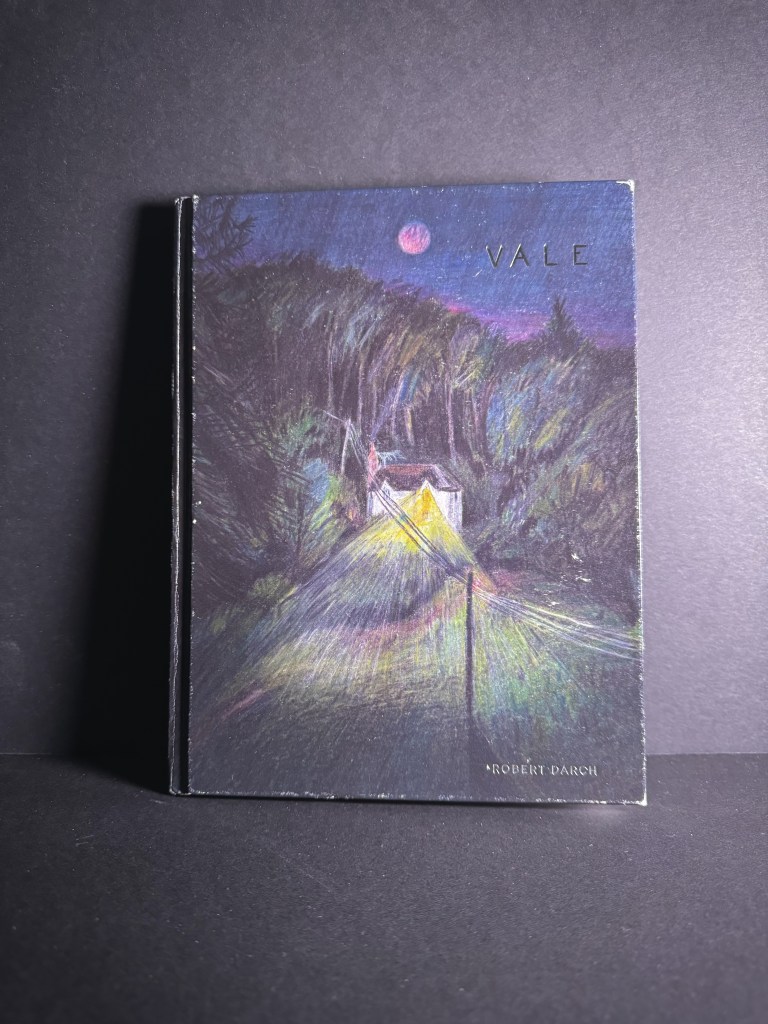

Vale is a beautifully lit mixture of reality and conjectured landscape, influenced by Robert Darch’s life experiences and his passion for films, television, literature, and painting. It is his second book, published through his imprint, Lido Books, in 2020. It begins with the look and feel of a landscape painting by John Constable: the sun rising and casting shadows through the mist and over water. The rustic bliss is then populated, somewhat uncomfortably, by a small cast of young characters, swimming in the river, walking uneasily through overgrown gardens to a house kept in a bygone fashion with moth-occupied, Egglestone-bulb-lit rooms.

Robert Darch (2020). Vale.

Darch’s first publication, Moor (Darch, 2018), analyzes places on Dartmoor, a National Park in SW England. In his latest book, The Island, he explores, this time in monochrome and again with portrayed characters, found places in the space of a post-Brexit Britain.

Quinn is a fictional story that transcends time and place. Written and photographed by Lotte Davies (Davies, 2021) it traces a journey on foot by William Henry Quinn from the south-west of England to the far north of Scotland during the aftermath of the Second World War. While Quinn’s appearance in the images, supporting films (this is a multimedia production) and carefully curated rural settings timestamp his journey into the 1940s, his post-trauma reflection and desire to rebuild his place and purpose in the world resonates with contemporary life in many ways.

Quinn is an impressive multimedia production that draws me in with its meticulous compositions, attention to detail and sense of place and time that would fit beautifully in a melancholically rendered episode of Doctor Who.

Lottie Davies (2021). Quinn.

Wuthering Heights

The wet and windy moors around Haworth, Yorkshire, are intimately entangled with the lives of Cathy and Heathcliffe in Emily Brontë’s only novel, Wuthering Heights (1847). Top Withins (also written by some as Top Withens), a long-time derelict farmhouse perched on the path of the Pennine Way, has, and will always be, linked to this romantic story and is visited by thousands of fans every year. Many tourists trek out of the village, past Lower Laithe reservoir and the Brontë Falls and take photographs in front of the ruins and the two knurled sycamore trees that withstand the airy blasts that are always there.

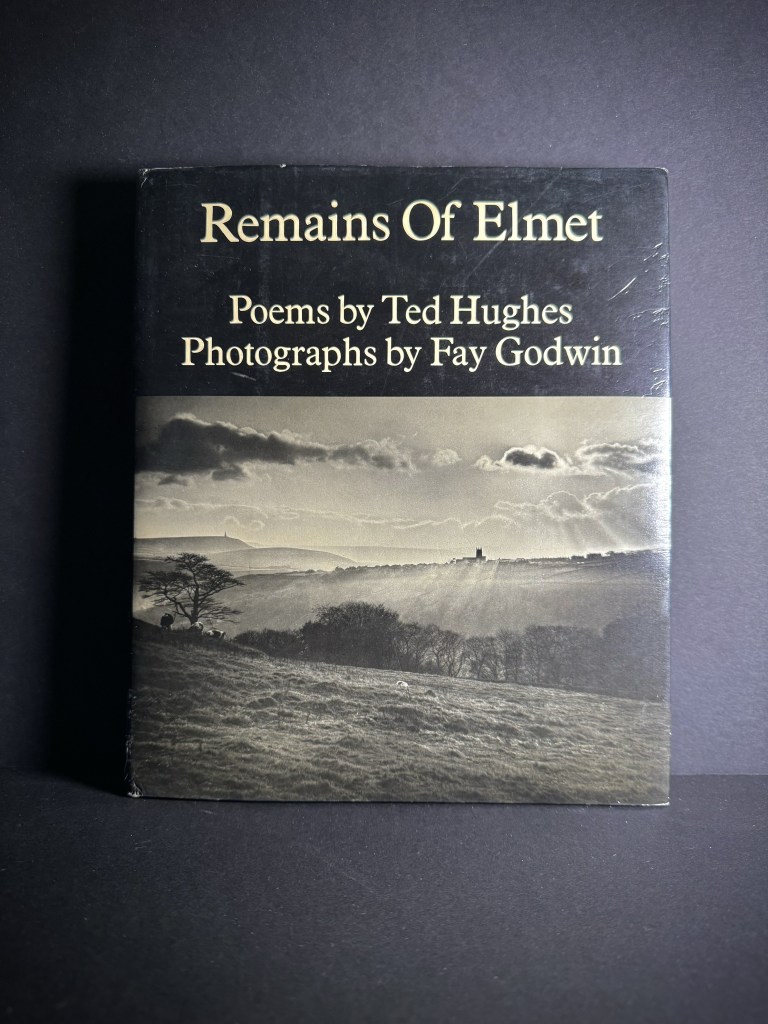

Celebrated photographers, including Bill Brandt (1904-1983) and Fay Godwin (1931-2005), also captured their version of this literary shrine. Godwin, Britain’s match with one of the most famous landscape photographers, Ansel Adams, photographed Top Withins as part of her words and images collaboration with Ted Hughes, who was Britain’s Poet Laureate from 1984 until his death in 1998.

Remains of Elmet (Hughes & Godwin, 1979) explores the people and paths, sheep and farmhouses, mills and chapels of this rugged millstone grit landscape around the Calder and Worth Valleys. There was a remarkable reciprocity in the making of this book, where some of Hughes’s poems were inspired by Godwins photographs, and some of his poems triggered ideas for more of her images.

Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin (1979). Remains of Elmet.

Their Place

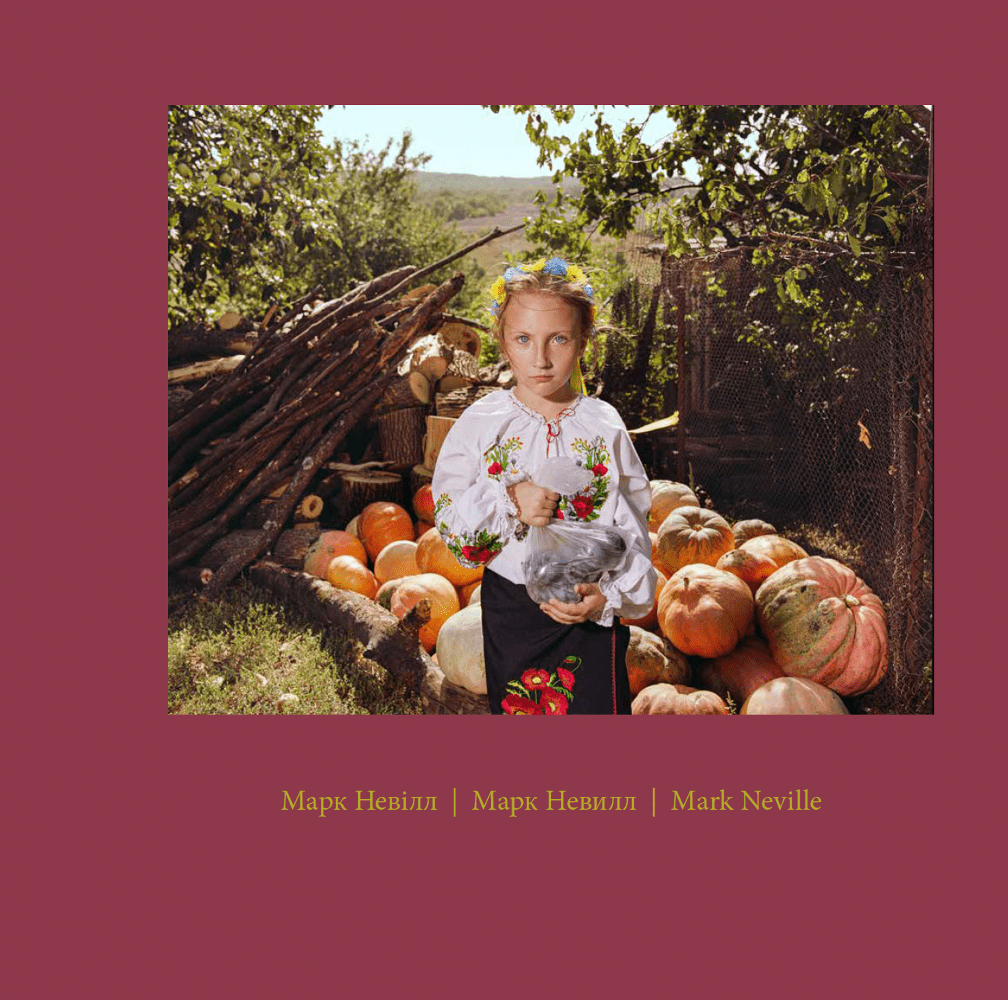

One of the most important aspects of Mark Neville’s work is his empathetic approach. He takes great care in making powerful, authentic community images and puts the people he photographs in the front seats of his audience. It is a highly commendable collaborative approach, a model for other documentary photographers to emulate.

Fancy Pictures

He has completed an impressive set of community projects, starting with The Port Glasgow Book Project (2004), which was “delivered exclusively to each of the eight thousand houses in the Port by the local boys’ football team.” Although Neville never made the book commercially available (he says his concept was “to undermine the framework of exploitation inherent in the way these types of images are usually disseminated.”), twenty-seven of the Port Glasgow photographs were included in Fancy Pictures, published by Steidl (Neville, 2016). This collection contains (amongst others) photographs from his second encounter with a Scottish farming community on the Isle of Bute in 2008 (also named Fancy Pictures) and images and writing (in conversation with David Campany) about his time as a commissioned war artist with the British Army in Afghanistan (The Helmand Work, 2011). That experience resulted in Battle Against Stigma, a body of work challenging the stigma of mental health issues in the military, which he also personally distributed to institutions and mental health charities throughout the UK in 2012.

Mark Neville (2016). Fancy Pictures.

Stop Tanks with Books

Stop Tanks With Books, Neville’s portrayal of life in Ukraine, was written and released just before the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022 (Neville, 2022). Complimentary copies were distributed to politicians, diplomats, celebrities, and the media to raise awareness and seek support for the withdrawal of Russian forces from Crimea and the Luhansk and Donetsk regions in the east of the country. All sad to say, that invasion has not gone away, and Ukraine continues to suffer deeply. Neville continues to live in Kyiv, where he runs a humanitarian aid and photography called Postcode Ukraine.

Mark Neville (2022). Stop Tanks With Books.

My Place

What does place mean to me? I was born and raised in Haworth, Yorkshire, lived, studied, and worked in several cities across England and Scotland, and then travelled internationally, including four years living in Peru and now in Calgary, Canada. That’s a lot of places that mean much to me! I will cover some of them in a separate story, but I leave you with a photograph of one of those places: Top Withins, through a millstone grit gate post, on the Pennine Moors near Haworth.

A millstone grit gate post with a view of Top Withins, near Haworth, Yorkshire. © J. Ashley Nixon

References

Alexander, J.A.P. (2020). Perspectives on place: Theory and practice in landscape photography. Routledge.

Angerson, J. (2019). English journey. B&W Studio.

Barthes, R. (1980). Camera Lucida: Reflections on photography. Hill and Wang.

Bate, D. (2016). Photography: The key concepts of photography. Bloomsbury Academic.

Bunney, T. (n.d.). FarmerFlorist. Another Place Press.

Bunney, T. (2023). Going to the sand. Another Place Press.

Burtinsky, E., Baichwal, J. & De Pencier, N. (2018). Anthropocene. Art Gallery of Ontario and Goose Lane Editions.

Coates, J. (n.d.). North Sea swells. Another Place Press.

Crespo-Lopez, M.E. et al. (2021). Mercury: What can we learn from the Amazon? Environment International 146, January 2021. Retrieved Mar 10, 2024, from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412020321784#:~:text=In%20the%20Amazon%2C%20ASGM%20is,Amazon%20(Galvis%2C%202020).

Darch, R. (2018). The Moor. Another Place Press.

Darch, R. (2020). Vale. Lido Books.

Darch, R. (2022). The Island. Lido Books.

Davies. L. (2021). Quinn. Mutton Row Books.

Ewing, W.A. (2016). Edward Burtynsky: Essential elements. Thames & Hudson.

Farnsworth, B. (2020). The International Affective Picture System (explained and alternatives). iMotions Research Fundamentals. Retrieved Mar 1, 2024, from: https://imotions.com/blog/learning/research-fundamentals/iaps-international-affective-picture-system/

Frank, R. (2019). The Americans (12th Ed). Steidl.

Hill, I. (n.d.). Lineage. Another Place Press.

Hughes, T. & Godwin, F. (1979). Remains of Elmet. Harper & Row.

Meadows, D. (2023). Book of the road. Bluecoat Press.

National Gallery of Art (n.d.). The Robert Frank collection: The Americans, 1955-57. Retrieved Mar 3, 2024, from: https://www.nga.gov/features/robert-frank/the-americans-1955-57.html

National Trust (2017). Places that make us. Research Report. Retrieved Mar 1, 2024, from: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/who-we-are/research/why-do-places-mean-so-much

National Trust (2019). Why places matter to people. Retrieved Mar 10, 2024, from: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/who-we-are/research/why-do-places-mean-so-much

Neville, M. (2016). Fancy pictures. Steidl.

Neville, M. (2022). Stop tanks with books. Nazraeli Press.

O’Toole, E. (Ed.). (2017). Anthony Hernandez. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Oxford Academic (n.d.). Shadow sites: Photography, archaeology and the British landscape 1927-1955 (Introduction). Retrieved Mar 1, 2024, from: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199206322.003.0005

Parr, M. (2017). The Last Resort. Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Sedikides, C. et al. (2015). Nostalgia counteracts self-discontinuity and restores self-continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(1), 52-61. Retrieved Mar 2, 2024, from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejsp.2073

Smith, W. E. & Smith, A.M. (1975). Minamata: Words and photographs. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Pingback: 24 pics from ’24 – NixonScan